“Bdihri Ma’etso”: Poems Of Profound Images

Once in college a poetry professor related to his students that traditionalist poets play down modernists by saying: “If you want to compose a modern poem, you don’t need a pen but a pair of scissors. You cut through a newspaper column; and a modern poem will be at your disposal.”

Being so much in love with the Romantic and Victorian poets, the professor himself didn’t try to open his students’ eyes so wide towards Modernists. As a result, if one doesn’t put extra-efforts on his own to know what kind of poems modernists composed, there is a big tendency to take the above statement for granted. When one indulges in the readings of modern poetry, the reason why modernists broke away from the traditional ways clearly makes shape.

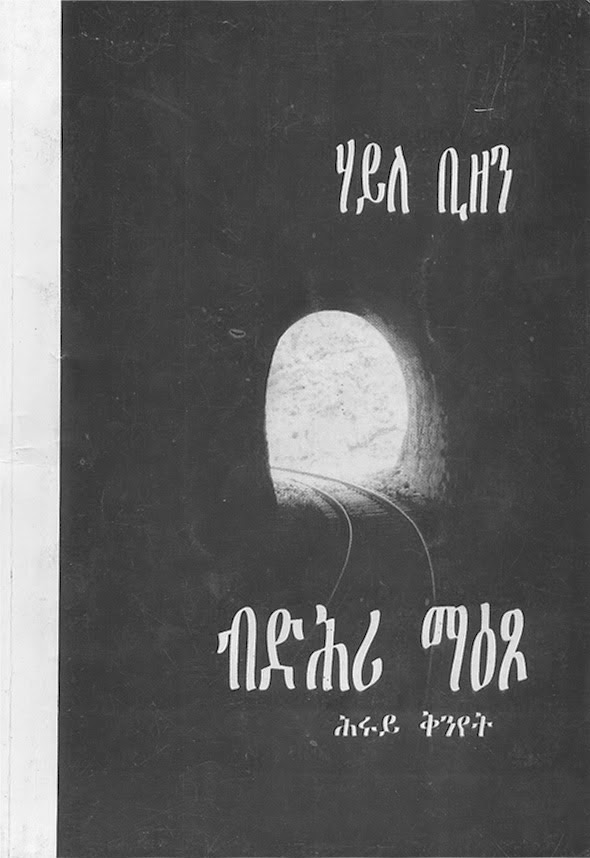

Anyone involved in a creative endeavour needs to proclaim his freedom of thought unrestricted by themes they deal with and forms that may not suit their voices. Haile Bizen with his “Bdihri Ma’etso: Hiruyat Qnyet” appears to declare the freedom of his voice unrestricted by form that is common and widely used in the country. Haile titled his poetry book “Bdihri Ma’etso: Hiruyat Qnyet” (“Behind a Door: Selected Tunes”). He calls his ingenious creations ‘tunes’, not poems. Therefore, reciting the 68 selected ‘tunes’ requires one to vocalize the melodies that could emanate from the form they are composed in.

The ‘tunes’ touch on many diverse topics. Some are dramatic monologues of inner feelings and introspection of human deeds and characters, also stages in human life; some deal with the sufferings of the Eritrean people under colonization; some are on places that are of national pride and beauty; and others are about heroism and sacrifices.

“Dimtsi Siqta” (“The Sound of Quietness”) could be taken an example of dramatic monologues of inner feelings and introspection. Its first two stanzas go (roughly translated) as:

“Dimtsi Siqta” (“The Sound of Quietness”) could be taken an example of dramatic monologues of inner feelings and introspection. Its first two stanzas go (roughly translated) as:At a time my shadow

Is drowned inside me

Mid-day

(it seems to me)

Wandering in a graveyard

Wandering thoughtless

Quiet

Clotted quietness

But that has

A sound

Scribbled loudness

This ‘tune’, in addition to intensifying the feeling one experiences in a quiet place by juxtaposing quietness with loudness, it creates visual and auditory images in the mind. Here, Haile’s craft starts with richness from its title using oxymoron figure of speech.

There are also a few ‘tunes’ that reflect stages in human life. “Dhri Mot Abokha” (“After Your Father’s Death”), “Hagegta N’esnet” (“The Fragrance of Youth”), “Bzey Aresti” (“Untitled” which I felt shows old age), and others. “The Fragrance of Youth” concisely reflects the age usually compared with fire; and a rough translation of the first three verses is:

Storm atop

Storm bottom

I’m in the middle

Right in the middle

Smouldering for straying

Desiring for straying

As stated above many of Haile’s poems reflect the bitter colonial period that the Eritrean people went through. Each of them is no less than the others. Weki, Shi’eb, Agordat, Onna and Massawa are some of the many Eritrean villages and towns that sustained the merciless hands of Ethiopian colonization. Haile has composed ‘tunes’ to many of them. Weki, a village a few kilometres northeast of Asmara, is one for which his ‘tune’ with very few words passes profound meaning about what happened there.

Weki (rough translation)

They know from old

and ancient days

Brothers struck by lightning

go to separate graves.

Other times

people annihilated by plague

go to separate graves.

In 1975

either the times changed

or the story they know,

Those massacred with bullets and bayonets

went to a single grave.

Haile’s ‘tunes’ for various places of history and other important places are also full of imageries that quickly sink in one’s mind. “Teatro Asmara” personalizes the theatre hall as a young woman at her best and a masterpiece in itself whether it staged plays or not. “Compscitato”, downtown in Asmara, symbolizes as warmth found after womb where everyone flocks there in the twilight. “Ane Habatsi” signifies Nakfa to have breathed life into man (Eritreans). “Emba Denden” gives the general setting of mount Denden where incomparable feats of heroism were accomplished. “L’eli Mqur Zmeqere” is about young Eritreans who joined the struggle for independence believing dying for the motherland as the sweetest of all sweet things. “Ab Qebrkhum W’ile” communicates with martyrs telling them that a mother letting springs of tears fl ow, a sister with hot smouldering tears and a young brother with an avalanche of tears pour inward; reading it placidly certainly make one imagine the flood of tears in Ghinda’e martyrs cemetery where the bodies of many fallen heroes was buried in 1995 (the year that the ‘tune’ refers).

The technique Haile employed in his ‘tunes’ suggest modern poetry in a number of ways. Of course, we find some of his works that take traditional forms of verses (not forgetting that Tigrigna poems have not been studied yet as to whether they have metrical pattern of composition or not). Many of his ‘tunes’, however, are free-verse that have their own forms, music, and rhythm. At times, he has used open form of poetry. Concentrating on the images his words create, he didn’t dwell much in perfecting rhymes. Instead, he has employed sentence rhymes (parallelism) that give music to his words when recited. For instance, the above stated poem titled “The Fragrance of Youth” and “Da’ela Meqabir” (“A Graveyard Humour”) can clearly justify that. The first few lines of “A Graveyard Humour” look like this:

Who are you?

Are you one of those who race to the pit

But who lost their point of departure

Or

One of those who got stranded on the pit

But who gaze at where they would go

Robert Creeley, a 20th century poet, is often quoted as saying, “Form is never more than the extension of content.” No different than this quotation, Haile Bizen has focused his attention to images. If we find carefully crafted forms of the poems, they appear to have spring out of their themes and the words that carry them. Almost all the ‘tunes’ instil in your mind some kind of picture. One of his memorable ‘tunes’ is “Bkha Ertrawi Kwenka” (“I Wish You were an Eritrean”):

Ravaged mom that was pummelled by suffering

That colonization thumped and was left toothless

Who lost her children like her teeth

Prayed restfully on independence

Imagists are also well-known for the use of assonance and alliteration, as well as diction that are colloquial but not artificial. Many of Haile’s ‘tunes’, however, lack these figures of speech — assonance and alliteration. His diction is, though, precise and sharp with poetic expressions that create clear and unforgettable images. In a number of his ‘tunes’, Haile has used mothers’ face to create such an image. Many of his words are contracted giving a voice that one can identify them with the way some people speak in daily life. This particular feature enables the ‘tunes’ to get easily achieved rhythmic music and enable one listen to the voice intimately.

Ezra Pound, influential American poet and literary critic pointed out that imagist poems should revolve around this points: “1) Direct treatment of the ‘thing,’ whether subjective or objective; 2) To use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation; 3) …to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in the sequence of a metronome.” Keeping this in mind, Haile Bizen’s “Behind a Door: Selected Tunes” could be taken as a pack of ‘tunes’ with profound images making him an imagist poet.